To Be Silent Amid Genocide Is Barbaric - Interview with Al Karpenter

I took a bit of time to talk to the members of the ensemble. Here you are

1.There is a moment in life for every artist and musician to get inspired and move on towards a certain direction and commit to start doing what is closer to your interest? You also have been through different stages in your life related to different genres. Can you describe this (those) moment(s)?

Al: Well, I started to write some things -and songs- in the mid 90s, but I didn´t advance in my musical formation till I bought a guitar in the mid 00s, that was my key moment. I started doing what I heard and saw from people like Sonic Youth, The Velvet Underground, Billy Bao, Eten, Liars -before they became electronic- or Captain Beefheart. That was the beginning.

Marta: When I was about seven or eight years old, someone rang the doorbell and left a vinyl record on the ground. It was a gift from a boyfriend to my older sister. It was a Hawaiian music record with a beautiful cover. My sister never listened to it. And that record was one of the first musical gifts I ever received. When I was seven, we went to a classical music store and they bought me the waltzes of Strauss. At ten, I was given a Suzi Quatro record and some Ennio Morricone records: For A Few Dollars More and The Good, The Bad And The Ugly. And if we add to all that the first time I heard Les Rallizes Dénudés, which exploded in my head with thousands of colors… I could also talk about Meredith Monk. Meredith Monk opened the doors to a fascinating world where voice, body, and noise were inseparable. And seeing Phil Minton perform Christian Marclay's Manga Scrolls was an UNFORGETTABLE experience!!

Enrique: Before joining the group, I already knew the work of Mattin and Al separately—they're both amazing creators. I had also worked with Al on another project, Delusion of the Fury. Now that I know them even better, they still keep impressing me.

I love this group. No limits, no rules—just commitment. And I don’t think we’re making music of the future. This is Al Karpenter, right now.

Mattin: For me, it has been about discovering music that tells you “it is possible to do that”. Back in Bilbao, discovering bands like Eskorbuto -who were reflecting the reality of the Basque Country at the time from a nihilistic perspective- coincided with my listening to The Velvet Underground and The Stooges, who shared a similar nihilistic attitude but were more avant-garde. What they all had in common was a rupture of hegemonic ideology by getting underneath the appearance of reality, showing its instability and fragility and exploring it to its fullest consequences.

Then, discovering improvisation -which pushes instability to its limits- felt like coming home. Combined with the disruptive power of noise, it seemed like the next step. Seeing AMM, Filament, Junko, Masonna, Fushitsusha, and Whitehouse live, and listening to radical electronic music like Maryanne Amacher and Roberta Settels, as well as very quiet music like Radu Malfatti and Taku Unami and more conceptual work like ZAJ and Walter Marchetti, was truly transformative. This conceptual approach helped me to understand each aspect of music—concerts, record production, cover artworks—as potential material for intervention from a different angle.

2. In your work you have different tools/instruments. How did you find your own way towards enjoying and using it for composition? How do you feel about it?

Al: We work with whatever instruments we have, and I sometimes make loops that become part of the mix. I usually play a guitar riff—either before or after—and then the rest of the sounds fall into place. For me, it’s a fun process.

Marta: My relationship with voice and instruments is rooted in deep listening and free improvisation. I studied piano, but I also play other instruments in a more physical, hands-on way. In Al Karpenter, freedom is at the core of the maddening music we create—edited by Mattin from a cave studio that somehow gets an amazing sound!

Enrique: John Cage said that everything is music—every sound, a fistful of sounds—it all depends on how you listen. In that sense, anything can be an instrument. On our new record, there’s eight-handed percussion on a contrabass box, kitchen utensil sounds, and both conventional and unconventional instrument noises. Post-production is fundamentally the key—it's the final and perhaps most important instrument we use.

Mattin: We might start with a conventional rock setup—voice, guitar, bass, and drums—but then we take inspiration from the Art Ensemble of Chicago and the Brillantene Dilettanten, in the sense that each of us plays whatever instrument we want. We record without fear, knowing that anything can become part of a song in the assemblage process of putting things together. There’s a kind of surrealist process at work—anything can find its place on an Al Karpenter record.

Except for Al, we’re all playing instruments we’re not particularly familiar with. We’re basically the opposite of professionals, so it’s not surprising that we’ve been compared to the Nihilist Spasm Band. We approach these instruments with a punk attitude—in the sense that you can just do it—and then we improvise.

3. Using certain technology to create music is a great idea but can also be a message. What drives you to create sounds using them? How did it evolve over the years of your personal experience?

Al: The message isn’t just in what you say—the way you say it is just as important.

Marta: I enjoy using any kind of technology—what matters most to me is the sound.

Enrique: There’s a message in every artwork—whether it’s intentional, explicit, or not. It’s the viewer or listener who interprets that message based on their knowledge, experience, or mood. Without an audience, there’s no artwork. Creation is always polysemic.

Mattin: I come from a background in computer music, but before that, I played in post-punk bands here in Bilbao. Al Karpenter brings those two interests together perfectly. What’s fascinating is how technology allows us to twist the rock format—something we love, but also find limiting compared to what noise makes possible. So we take the freedom of the latter and apply it to the former—and we have a blast doing it.

It’s interesting that we often rehearse in Bilbao, a post-industrial city, and our music has also been described as post-industrial. Al Karpenter reflects some of the contradictions of Bilbao’s contemporary urban landscape. What was once a rough industrial city has now rebranded itself as a neoliberal model through cultural marketing and technological innovation. But in doing so, it tries to conceal its struggles—yet those struggles keep resurfacing. In Al Karpenter, we take inspiration from these struggles and use technology to make music that belongs to a culture that cannot be easily defined, instrumentalized, or marketed.

4. How do you set up for your live gigs? What approach do you have in terms of composing?

Mattin: The composition mostly happens in post-production. For live concerts, we sometimes rehearse in Bilbao, sometimes online, and sometimes right before the show. We basically adapt to whatever situation we're in. Improvisation is a key part of what we do, so there’s a lot of openness—but always with a strong sense of precision and intention.

Al: Yeah, it’s not easy for us, but we give it our best—and that’s what matters. Every moment we get on tour, we use it to rehearse and prepare for the gigs as well as we can.

Marta: It’s easy to prepare for the concerts—there’s a great vibe between us. Ideas just keep coming and coming and coming...

Enrique: The whole group is on the same wavelength. It’s very easy for us to start working, and we have a great time. Traveling to perform in different places is also a good reason to explore other shared interests: art, gastronomy, and other forms of culture.

5. How did you feel about collaborating with anyone before you met? What brought you together and how did you find the communication? Can you tell us a little bit about working with different artists?

Al: This project has been going for over 20 years. I was already “Al Karpenter” when I played with Karpenters—now Krpntrs—with Bárbara Lorenzo on drums in the early years. The first works under the name AL KARPENTER—which are available online on platforms like Archive, SoundCloud, Vimeo, and YouTube—included collaborations with people like Mikel Xedh, Héctor Rey, Jorge De La Visitación, Ainara Legardón, Enrike Hurtado, Oier Iruretagoiena, Ulzión, Txemi Artigas (Mr Smoky), and others.

Mikel Xedh was a big help to me in those early years—around the beginning of the 2010s. He gave me the confidence to feel at ease with electronic forms. That was a key moment in shaping Al Karpenter’s musical identity.

Marta: For me, playing with someone I don’t know is about connection and active listening—it can be magical at times. When I discover interesting music, I imagine myself making those sounds alongside the person creating them.

Enrique: Our experience with different musical styles allows us to challenge everything freely, without seeing our limitations as a handicap. Improvisation is all about listening—to everyone else—and knowing how to act, or when not to react and just stay silent. By doing that, we can navigate any idiomatic challenge without difficulty.

It’s simple: pay attention, listen, and speak only if you truly have something meaningful to say. Working with others teaches you a lot—it’s a great antidote to narcissism, ego, or a superiority complex. A kind of therapy, really.

I played live with Mattin and Al in a project called Érzsébet—at the Zarata Fest over 12 years ago, with Mikel Xedh, Alejandro Durán, and many others. So when they invited me to join Al Karpenter, it was a truly surreal moment!

Mattin: We all come from many years of improvisation, so we’re very comfortable collaborating with others. For example, the record we did with CIA Debutante came out of a one-day session in Berlin, which was an incredible experience. We’ve also collaborated with Sunik Kim, Dominic Coles, and Triple Negative on The Forthcoming. The early records also emerged from many collaborations—with María Seco, Joxean Rivas, Chie Mukai, Lucio Capece, Werner Dafeldecker, Loty Negarti, Seijiro Murayama...

On our latest record, we have contributions from Lisa Rosendahl, “ ” [sic] Goldie, and Mikel Xedh. Sadly, Mikel Xedh passed away at the beginning of the year, which was a major loss for the experimental music community in the Basque Country. He was a true catalyst. Our last album is dedicated to him.

6. In an ever changing distribution of music how do you see your place and how do you feel about physical releases?

Marta: I love physical editions—LPs and cassettes. The objects themselves, and the sounds those formats carry, are truly marvelous.

Al: Well, it's really difficult to release music in physical formats these days—LPs, CDs, even cassettes—but it’s always been a strange kind of career. I feel lucky every time a record label shows interest in publishing our music.

Enrique: Today, there are many ways to publish your music, and it can potentially reach a wide audience. But the issue is that the profitability you get from it—within a savage, capitalist merchandise distribution system—acts as a form of censorship. It’s something the philosopher Herbert Marcuse already pointed out back in the 1960s, sixty years ago.

Mattin: I remember Steve Albini once saying that vinyl wasn’t just nostalgic—it was a format grounded in material reality. Sound is literally cut into the grooves of the record. It’s like a material crystallization or condensation of a specific moment in time, becoming a kind of message in a bottle—you have no idea where it will end up. In contrast, it's easy to imagine digital files ending up on broken hard drives, discarded and sent for recycling. If aliens landed and wanted to understand human recorded sound, vinyl might actually be the most intuitive place to start.

We’ve been lucky to work with labels like Munster, ever/never, Crystal Mine, and now Hegoa Diskak and Night School—labels that genuinely care about the music and the records they release. They take huge risks purely out of love for the music. The situation is incredibly difficult, but there’s still a strong independent network of shops and distros keeping things alive. As long as that network exists, we’ll continue to release music in physical formats.

We honestly don’t know what might happen with internet platforms—some of them are great, and it’s incredible to have this level of global distribution and accessibility, but things can quickly turn ugly without warning. For example, in February 2024, SoundCloud quietly updated its terms to allow uploaded material to be used for training AI models, without informing artists directly. Although they later revised the policy to require explicit opt-in, the incident highlighted how easily platforms can shift direction without transparency.

That said, there are platforms trying to be more conscious about these issues—like mirlo.space, subvert.fm, and ninaprotocol.com. And we always have archive.org.

7. Could you tell us a bit about your latest work?

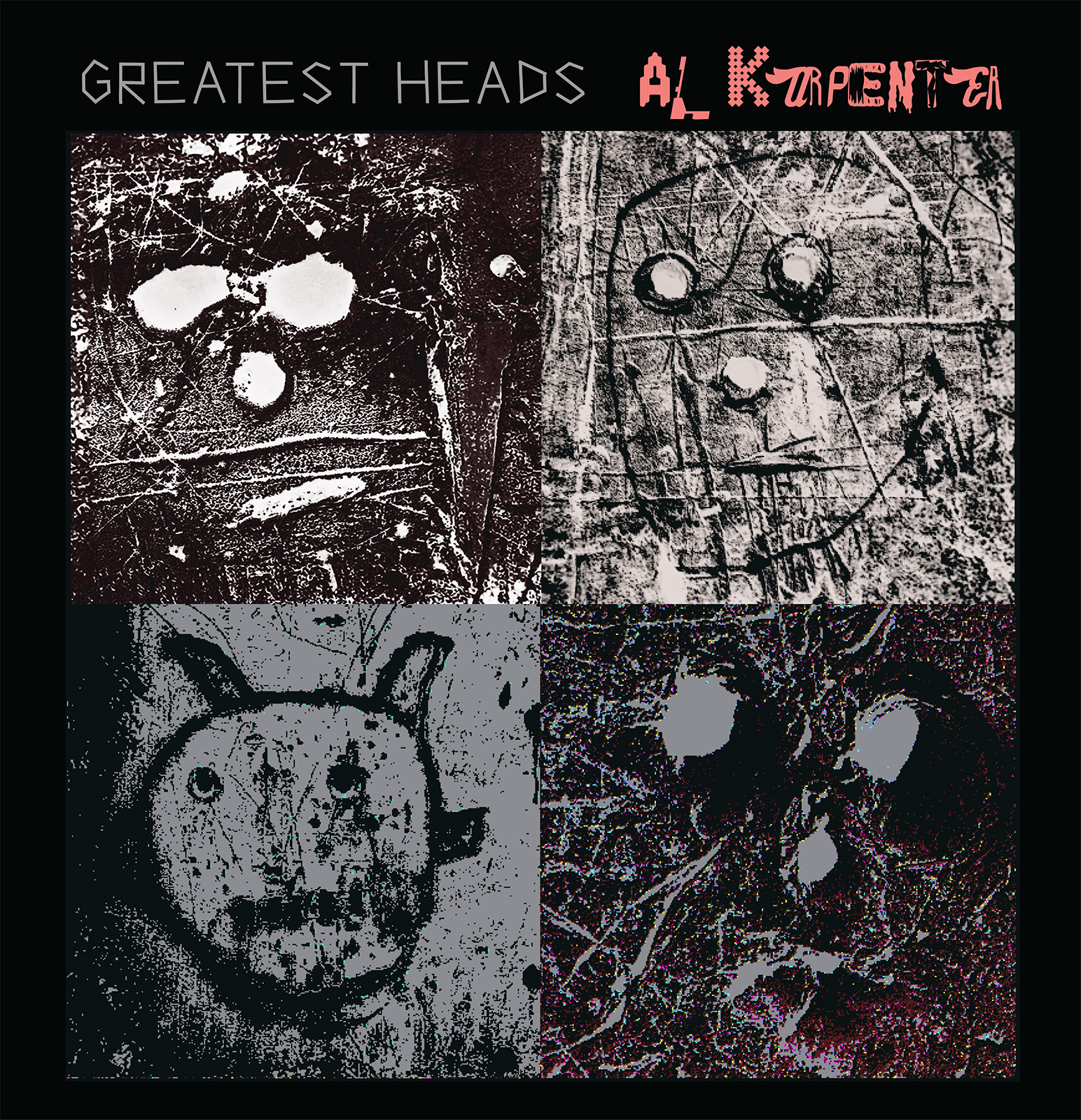

Al: We tried to make the most eclectic and open album as possible with “Greatest Heads”.

Marta: I like what Nathan Roche (CIA Debutante) said about our last record: -“It sounds like you all went into a deep, deep jungle and got hypnotized, or cured by many rituals by an unknown prehistoric tribe, that oddly enough beyond our level of conscious... l love all the production work, it really takes you on a unique sonic journey ... ”-.

Enrique: Of the four records we've made with this lineup, this one might be the most solid. We've grown in our ability to better express the musical concepts that interest us, and also in our capacity to let go of preconceptions and experiment in different directions.

Mattin: Our latest record might be our most mature and complex—a synthesis of ideas we've been working on, like decentering the rock song and transforming it into something else. Hopefully, it's a recording of abject contemporary reality that still contains a latent possibility—a statement that things can be different by being something different. It's a rejection of the status quo, of resignation, of fatalism.

Adorno wrote in 1949, “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” So when we asked ourselves what kind of music can we make in the face of ongoing genocide, we knew it couldn't be acritical or complacent. It has to push itself—to break form, to rupture comfort, to carry dissonance as a form of truth-telling. It has to refuse indifference and insist, in its own fractured and noisy way, that another world is still possible.

8. Plans for the future?

Marta: Making music is a kind of happiness. I’m lucky to play with musicians I admire and love. I hope to keep creating different noise recordings with them—and I absolutely love playing live! It’s wild and addictive!

Al: Yeah, the plan is to keep enjoying the ride—to work on a new record (we already have a working title and some fresh ideas) after the upcoming gigs. And for myself, I’ll keep running a few parallel projects I’m involved in, like 3l P3rr0 V3rd3, Krpntrs, The Heart Junkies, NUZ, No Jump!, and Videofan.

Mattin: Our next record will probably be called Where Is This Lunacy Going to End?—or simply Lunacy. We’ll try to respond to this almost impossible question—where is this insane phase of the world heading?—by pushing the power of making music together as a way of saying: we’re here, we’re alive, and we’re not going down.

Enrique: Working in this band is always a challenge—a constant search for new ways of expression without limiting our creativity. We make no compromises except with ourselves and our own perspective on how we see things and relate to the world today.

Coming together to play or record is always exciting—we never know what’s going to happen, but we know it will be interesting.

We’re rhizomatic.

Anti-Copyright

Photos are from the concert at Cafe Oto, on the 16th of February 2024, the line up was Al Karpenter, Damp Misery (Paul Hegarty & VOMIR) and Billy Bao.

Credits: Gabrielle.

Comments

Post a Comment